Activity Report: On Ed Park's new novel, Same Bed Different Dreams.

A sidebar to my review of his novel that is at least as long as my review.

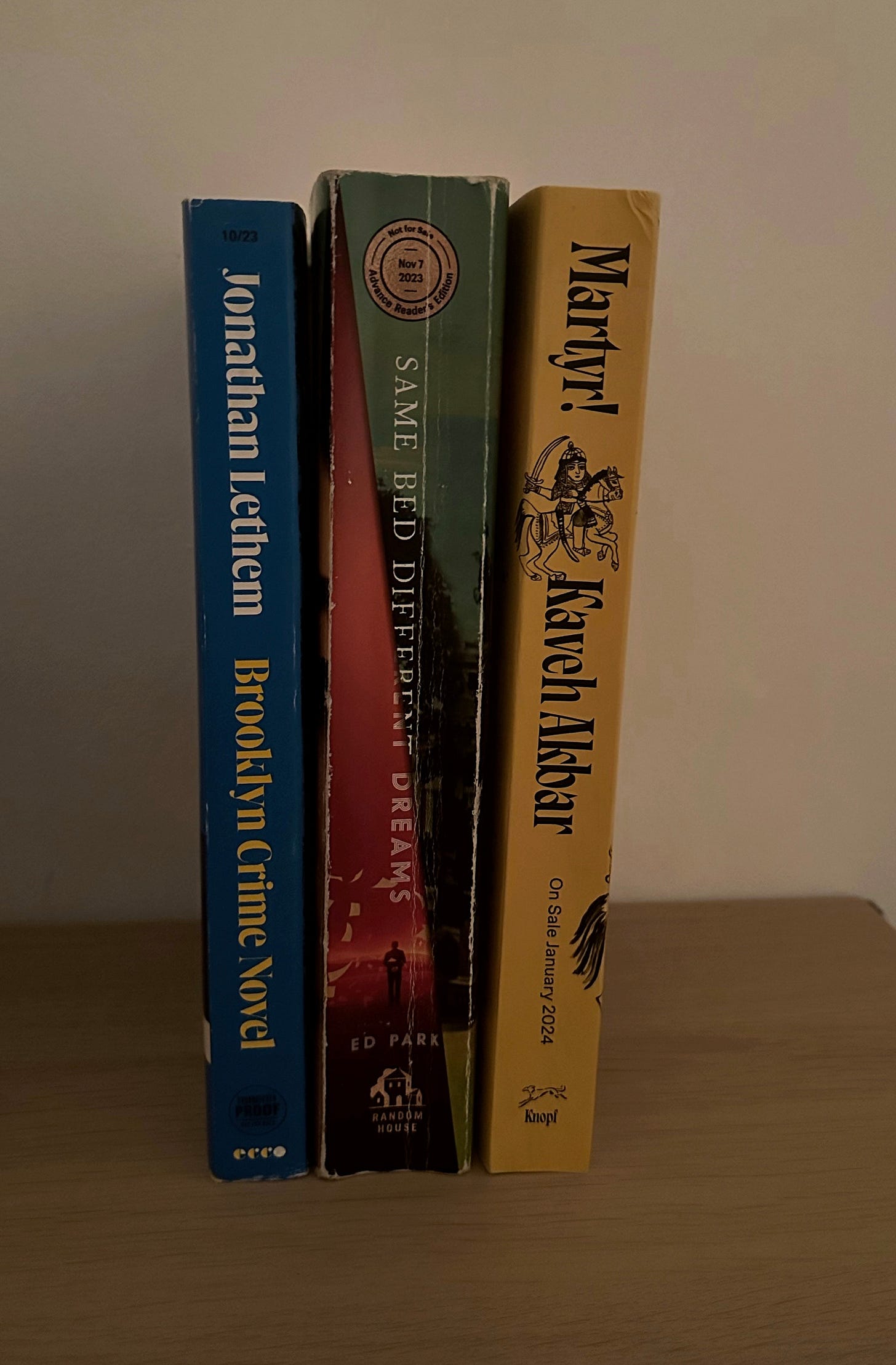

This photo is my only photo in my archive of the galley for Ed Park’s Same Bed Different Dreams, which I reviewed for the New Republic as I mentioned in the last installment, one of my major accomplishments from last fall. I think of this as like the book galley version of one of those magazine ads where the model has a date on each arm. And these three…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Querent to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.