American Letters 4 - The American Bibliomane's Survival Guide

On chasing the quiet he feels in bookstores. And hosting a Halloween reading for Lucy Ives.

He feels the quiet as he enters the Norwich Bookstore. Not so much the relative quiet of the bookstore but a quiet inside of himself. A way time slows down. His heart also. This is just how he is at bookstores, how he has always been ever since he was a child and used to ask his mother to leave him at a bookstore while she did her shopping errands at the mall. And she did. He spent many hours reading on the floor of the bookstore, crosslegged, his calves going numb.

For nine years he did that, from age seven until he could drive himself to the mall nine years later and sit in the bookstore on his own schedule.

He had greeted one of the owners who was just outside with her husband and business partner, himself now wheeling a huge bin away from the store to mail off signed copies of The Big Book of Bread. “I’m here for a treat,” he tells her as she re-enters and greets him, and she points to a copy of a book on the wall with a huge loaf of bread on the cover. “How about a book about bread?” He doesn’t bake much but he knows someone who does, and tells himself it is for her as he sets it on the counter. But maybe he will be a baker next. Who knows? The cookbook is gorgeous.

He came in looking for a few books. The first was a physical copy of Anne Carson’s Wrong Norma—the digital he bought impulsively a few days ago when he couldn’t wait even as long as it took to wake up and drive to the store is like reading a euphemism, he understands, after he takes the physical book in hand. He then asks after a copy of Jeff VanderMeer’s new novel, Absolution and adds that to his stack. Also Mosu Abutoha’s Forest of Noise. Out of stock.

Another installment in the third person letters series. For the story thus far, check out American Letters 1, American Letters 2 and American Letters 3.

As he walks the bookstore and thinks about what he’ll buy he is aware this is a place he slows down enough to have a little dream about his life. He indulges in a dance of idealized selves with each book he passes. People call their stacks of books at home a TBR—To Be Read—but it is really more of To Be Next, a chaotic portrait in many pieces of who you might become. This year year he knows he’s been buying many books, maybe too many. His editor came by for lunch over the summer and remarked on how she wished she had a library of contemporary fiction. When his husband asked him the day before about adding a bookshelf to the foyer, he realized it is one of the few walls where he doesn’t have bookshelves. He likes the space. He likes it empty. Could he pull back, he wondered.

“I don’t mind,” his husband says to him of the books gathering, well, everywhere. They arrive by mail also, sent to him, advance copies, copies sent with the respect of the author.

But the writer he is knows something is wrong. That he is in the grip of something. A bibliomania, one legitimized by his role as a professor of literature and a writer and critic. It’s all research, right? He’s been enabled by his research funds, and as a result, has spent 8 years feathering the walls of his house with books. Also his office on campus and his office upstairs, the spare bedroom, the basement. Also his writing shed in the back yard where he’d said he’d have no books.

He wonders if he is chasing off a sadness, building a fortress of books that can’t shield him from the grief and chaos of the year.

As a child in the library, where he spent many hours, he was hiding from classmates he hated. They called him a racist insults, said his face was flat, made fun of his being from Korea, a country they had the privilege of not knowing about after America had first effectively conceded it to Japan way back in 1905, in secret. Korea, Japan, same difference. He didn’t know enough then to be as insulted as he should have been.

Is he building his own library now, in his home, some instinct from childhood, he wonders, as he puts another bag of books in his back seat and drives home.

The next morning, he puts two boxes of books to donate into the car where they wait still. The year before last he had a birthday party and sent everyone home with a book. For a few years he had a box outside his office of books that said PLEASE TAKE. He also has put them on the table for free books in the downstairs of his office building. Sometimes he gives them to a friend, who now has a table like his in her house, covered in the books he’s given her. Sometimes he puts them in the little free libraries in Hanover.

*

He hosts a Halloween night reading on campus for his friend Lucy Ives, who reads an excerpt from an abecedarian essay in her new book of essays, An Image Of My Name Enters America. She is dressed, she says, as the Beautiful Void of the Universe, wearing a dark dress covered in planets, her face also done in makeup to contain, very faintly, shooting stars and planets also. She wears magnificent high-heeled boots for this. He has donned a black leather mask his friend

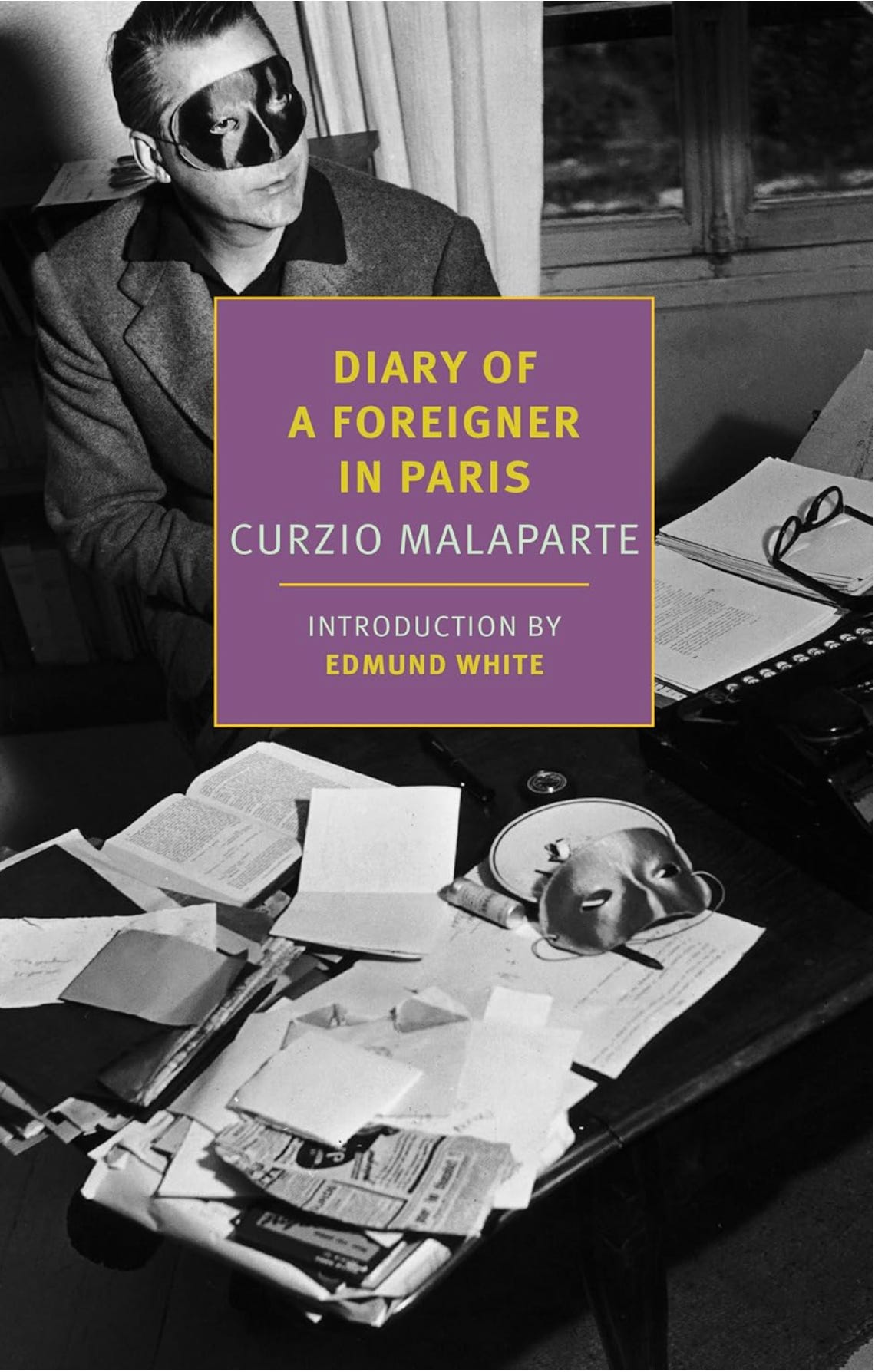

gave him when she moved out of her Brooklyn apartment for New Orleans, a favorite object. He has dressed in black jeans, a black t-shirt, a black linen shirt over it but does not have a particular idea in mind for his costume. He could have done more say to resemble Curzio Malaparte in the photo on the cover of Diary of a Foreigner in Paris. He loves that photo. But on reflection, Malaparte’s mask is satin and his is leather, and all he really wants of Malaparte’s life is his incredible house. An easy thing to want because it is impossible.And there is never really a good time to dress as a Fascist for Halloween.

In any case, everyone says the mask suits him, which pleases him. A student asks, “What are you, some kind of superhero?” Because earlier in the day he teaches class in the mask also.

“No,” is all he is able to say. He wouldn’t say he was. He just didn’t want to leave the house without a mask and there it was, in his husband’s special leather box where he keeps it. On one of his bookshelves.

Later that night his husband will send him Peter Hujar’s Boys In Cars, Halloween, 1978, and it feels like a better guide. His costume like a sequel to the boys in the photo. An I Hate Gay Halloween meme.

*

Lucy’s reading is accompanied by an elegant slide presentation she has created that is nearly cinematic. A powerful lyric moment is conjured there in the library and as she reads some other sounds of the campus come in through the windows, left open because it is 70 degrees that day, warmer than Halloween there normally ever is. The essay describes a time when the young person Lucy was felt sure that the world was ending and would end, in her lifetime. She describes this in the essay while outside some members of sports team sit down with a musical instrument and begin playing a song one of them is singing—they are sent along amiably enough by the admin—and from across the green, the chants of a protest of Mike Pence’s appearance on campus can be heard. But Lucy continues as if all is ordinary, the reading is not somehow obscured by the ambient noise but instead focused by it and the audience hangs on each word. It is a powerful principled introduction to the vulnerability she felt then, an evocation of it also, and as he sits in the audience to see the slides he is proud of his friend, whose book he loves very much.

He asks her to describe the process she went through to write the essays, as she conceived of the book as an entire whole. She sketches that out for the audience, and then he asks later how it feels now to have done this, what it is like. This is emotional for her, she says. To consider. “I feel like this could be done, this experience of my life could be described,” she says. This was not something she believed when she was younger.

The audience Q&A after is focused in large part on the abecedarian in part, which people ask about but also fear pronouncing. He sips on some apple cider and as the event ends and he watches people get their book signed by her, he is happy that this is part of his job.

*

Hopelessness is dangerous because it is an abandonment of your own power, he wrote to himself in a note that day.

Put this in the newsletter, he tells himself.

He does.

Thank you for putting in words the compulsion to collect books as some kind of bulwark against the pain of childhood…I feel that so deeply and have never been able to articulate it.

“…feathering the walls of his house with books…” Dreamy imagery inspiring me to visit the peace and insulation of my bookshop today. And to buy a new bookshelf.