“How do you know what to read?”

A question from a student in 1993 that I could keep answering.

Her question, asked with the vulnerability of an 18-year-old student who has just finished her first term at the University of Iowa, endeared her to me. How did I know? Did I know how I did it? I realized I’d never once described it for anyone. This question came at the end of my last class in my first rhetoric course taught as a graduate student, a part of my deal at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. As I thought of my answer and how strange it was to struggle with an answer to this question, I knew I would have to articulate something that had become second nature to me. I had learned pedagogy for the first time to teach this class, a pedagogy that has informed my teaching ever since. As this question also did.

I ran through my memories of my life of hunting for something to read. A browser’s life. A boy who was determined to put his name in the back of every book in his school’s library, like an ambitious soprano imagining herself in her city’s every theater. I made my mother leave me at bookstores when she went to the mall, and waited for her at the library when she picked me up after school. I read books I found while babysitting or in friends’ summer camps, also their old New Yorkers.

By the time I got to Iowa, I was walking after classes through the used and new bookstores in the town, looking for books even casually mentioned by my professors. And while I didn’t always buy them, I did examine them. I opened them, read the first page, read a few more, and if I felt reluctant to put the book down, it left with me, if I could afford it. I described this for her and she nodded.

I then told her about asking favorite writers at readings who were they reading. If they included an epigraph, and it struck a chord in me, who was it by? In the acknowledgements of favorite books, what writers did they thank?

But there was much that I did not describe that would be very apparent to me in retrospect, invisible to me at the time, my pattern of life: my apartment full of un-recycled copies of the New York Times Sunday edition, so many that I was able to use them to surround my bed when my basement apartment flooded at the end of that first year of graduate school. The stacks of my old New Yorkers, saved if I loved something, like Joan Didion’s “Trouble In Lakewood,” or Janet Malcolm’s “The Silent Woman,” or a new Deborah Eisenberg story, or this excerpt from a novel by Michael Cunningham or this one, from Chris Adrian, a classmate, “Every Night For A Thousand Years.” I still have a folder in my files of the stories my professors gave out in class, the old photo copies now 30ish years old. Still hanging on. Even mentioning them here makes me want to go pull them out. That folder growing slowly over the two years I was there.

There was also the comic shop. I have two copies of the original first printing of David Wojnarowicz’s Seven Miles a Second, bought in the comics format he’d wanted. I had also learned these stores usually sold zines.

I also did not describe taking The Iowa Review magazine class during the review of the magazine’s archives, where we decided what would be included in the anniversary issue, and in order to do so, were given the entire 25 years of the magazine up to that date. I would move back to New York City with them, stacked in boxes like they were treasure, and I kept them for many years. I deeply regret selling them ten years later before a move to Los Angeles.

And I did not describe going to the part of the used bookstores where they kept old literary magazines. There I found more treasures, like the New American Review, back issues of Grand Street or The Paris Review.

This was before the internet—before the online archives. I was hungry to read, hungry to know, hungry for what these old magazines had inside them—the art, the interviews, the poems, the stories, but also the harder to define sense of a literary magazine as a kind of cabaret on the page, a variety show unfolding as you went. I kept these back issues, looked for them, because there was no other way to find what was inside the magazine. What if the writer never collected their essays or stories or poems? What if that magazine publication was the only time it appeared and I loved it and needed it? I was just being pragmatic.

I did not describe going to the college bookstore to buy books after the term had started from classes I found interesting but did not take. And I did not describe haunting Prairie Lights Bookstore, chatting with the booksellers just about every day of my education there. Or the Village Voice’s literary supplement, the VLS, my favorite of the reviews, whose closure, back in the 1990s, felt like a loss I’d never get over. I suppose I haven’t. In a way I spared her that.

*

Now it is 32 years later. A colleague mentioned when visiting my home that most of the books seemed new. A friend said the same, an editor of mine also. This is because I have been spending that academic funding. After a life lived as a visiting writer, for 20-some years, I do have tenure, and so as I don’t have to move every year, and as I am no longer confined to owning just the books that could fit in my New York City apartment, I am a madman about it, really—a bibliomane.

Not all of the books are new. Just new to me. Some are restored. There is a used bookstore near me that seemed to contain many of the books I somehow lost track of over the years, like Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day, as if the store inventory itself was prepared to help me build my library up again. Alongside the new books are some Black lesbian literature I was missing from the old days, like Cheryl Clarke’s poetry and Becky Birtha’s story collections. I found a copy of Home Girls, the Black feminist anthology Barbara Smith had edited back in 1983, and even an old galley of Andrew Holleran’s Ground Zero, his collection of essays published during the first years of the AIDS pandemic.

I am still a literary magazine nerd. I celebrated getting tenure by purchasing an entire print run of the defunct literary magazine Antaeus. And when a friend mentioned having a run of Granta magazine issues she was going to get rid of, I bought those too.

32 years later I can say I was and am helped by anthologies. The ones that include me and the ones I regularly aspire to be in. The Best American Essays, Stories and Poetry anthologies, especially, which I learned to comb for work that excited me, before examining the back pages, the lists of the noteworthy essays, stories and poems, and the magazines that would publish them. I use them as a guide to submissions and subscriptions.

My favorite editions have traveled with me for decades and the writers I found there are favorites to this day. When I edited the 2022 edition of Best American, I went back to these, to remind me of what I might be looking for. Anne Carson’s essay, “Kinds of Water,” found in the 1988 volume, became an essay I read every year for a decade: a description of her journey on the Santiago de Compostela pilgrimage in Spain, it was its own education in longing, and the ability to make sense of yourself on a journey undertaken in relationship to that longing. “The Meteorites,” by the late Brian Doyle, was another such essay, with a tender lesson in it about friendship, love and summer camp. Franklin Burroughs “Compression Wood,” almost impossible to summarize except that it is about living when you are split between one place and another, and what can happen to your thoughts as you travel between those places, is another favorite. And “On Seeing England For The First Time,” by Jamaica Kincaid, in Sontag’s 1992 edition of Best American Essays, blew me away, raising my standards for myself as a writer and making me her fan forever. I was already a Hilton Als fan by the time I read his essay “Buddy Ebsen” in the 2011 edition, but it sealed me to him a little closer than before. And I still remember finding Didion’s prescient essay “Sentimental Journeys,” on the Central Park 5, also in Susan Sontag’s 1992 volume, bought as I began graduate school that fall in Iowa.

I am a speed reader, trained as a child on a machine in the 1970s that projected sentences on the wall at increasingly high speeds. I did not master skimming because it felt like dissociating, where as reading fast felt like excitement. But also for me this reading is like drinking water or coffee, activities I find pleasurable and necessary. I am someone who reads an average of three to four essays a day for fun, usually online, even while teaching, and I find the essays often but not always on social media. Being without my Twitter network now after leaving the site does feel a little like being lamed. But I manage. And I do subscribe to roughly 30 literary magazines, in a mix of digital and paper subscriptions, and most if not all of these subscriptions come with access to the publication’s digital archives, the subscription paying for more than the issues that come in the mail. The Paris Review, The Sewanee Review, VQR, Harpers’, The London Review of Books, The New York Review of Books, The Yale Review and The New Yorker. I also use JSTOR frequently, which my students can access from their institutional libraries, and which does allow people to make accounts for free, and which has extensive archives of essays, stories and poems published in many literary magazines that do not otherwise have online archives, either because they cannot afford it or they are defunct. And Literary Hub reprints the work in many literary magazines typically for free.

I also read newsletters, too many, but I subscribe to too many to count, a mix of free and paid, on here or elsewhere. I treat them a bit like favorite local bars I dip into more than something I read entirely. I am not a completist about my newsletters and I don’t think anyone could or should be.

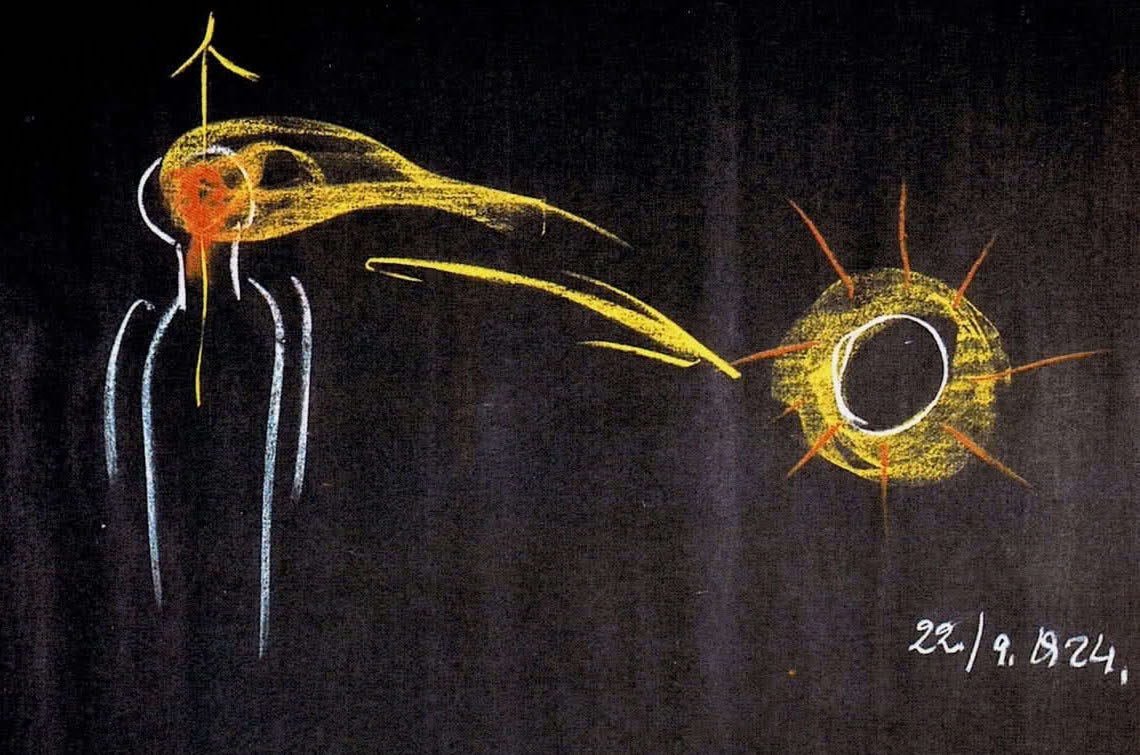

“Rudolf Steiner Blackboard Sketch,” via Wikimedia. {{PD-US}}, via the essay The Warburg Werewolf at the Public Domain Review. The essay is partly about a Good Neighbor classification for organizing books, which I can’t adopt but do understand. Anyway, this is illustrating what my mind looks like as I browse a new book.

Look over your bookshelves or even the last five books you’ve read. Is there a pattern? What is the pattern? Are most of the books you’ve chosen recently published? How many of them are by writers you have never read before? Who published these books? How many are in translation?

In 2019 I wrote about diversifying your bookshelf by beginning with an audit and I think that’s still a good idea. What are you not reading, is a good question to ask, especially if you feel like what you are reading smacks of a sameness.

I go to a number of bookstores I love because I feel, when I enter, that I could never live long enough to read all of the interesting books. Recent visits to Three Lives in New York City, as well as Books Are Magic, PT Knitwear and McNally Jackson, or Pulp in Montreal, or Moon Palace in Minnesota, or Book Moon in Northampton, MA, to name just a few. Locally here in VT, I divide my time between Norwich Books and Still North Books.

I follow favorite bookstores on social media and their booksellers, too. Some of them are also critics or writers themselves. This is something I learned to do because once upon a time, I was also a bookseller who in his spare time was allowed to use the store computer to write his freelance articles. Stephen Sparks for example, of the wonderful store Point Reyes Books, out in California. He obviously curates his whole bookstore but his impressions as a reader are always helpful.

And of course, my local library. It is the one at the college where I work, exceptional at buying new books.

These are just a few things I do to make sure I have enough to read. What about you?

I loved this so much.

"I celebrated getting tenure by purchasing an entire print run of the defunct literary magazine Antaeus." -- this is the perfect celebration.

Holy wow. Deeply inspiring and also consoling.