I Want More Of You In Here: A Guide to Interiority In the Personal Essay and Memoir

What To Do When They Ask For More Of You

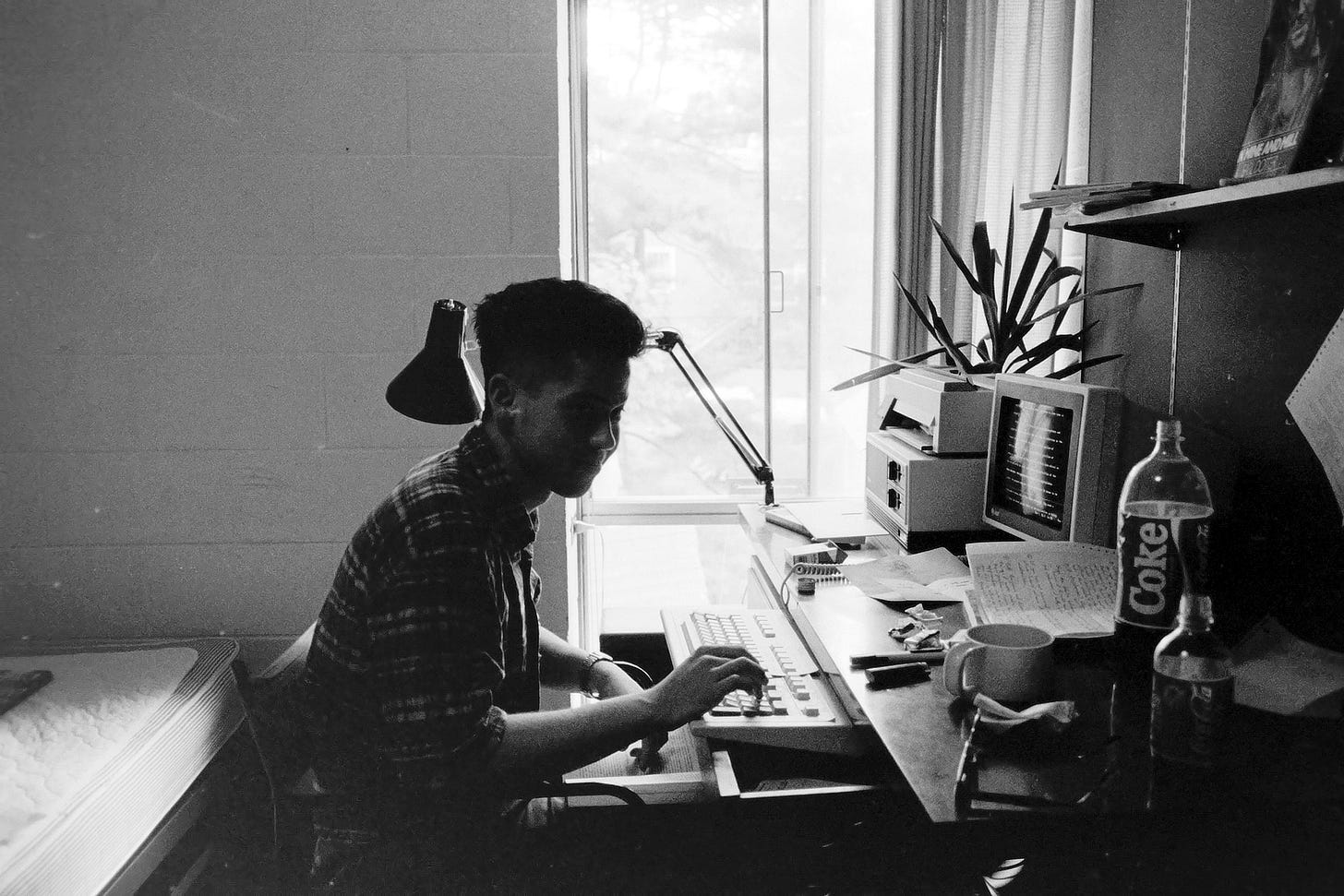

A photo of me at the age my students are now, trying to do what they are doing now.

I have been teaching my writing students in my essay class to write about their feelings. This is a challenge for every writer, including me. I write in part to discover what I feel, and have traditionally done so since I was, well, the age of my students. I recently aske…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Querent to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.