Some thoughts on teaching the writing of speculative fiction.

It’s been a difficult time and I think ever since Solmaz Sharif posted WHAT WILL YOU TEACH on her Facebook back on November 9th, 2016, I have come to a new understanding of the way teaching helps me keep going in the face of tremendous pain and uncertainty. Or as Lynda Barry says in What It Is, "We don’t create a fantasy world to escape reality, we create it to be able to stay."

I generally teach a class to think about something with other people.

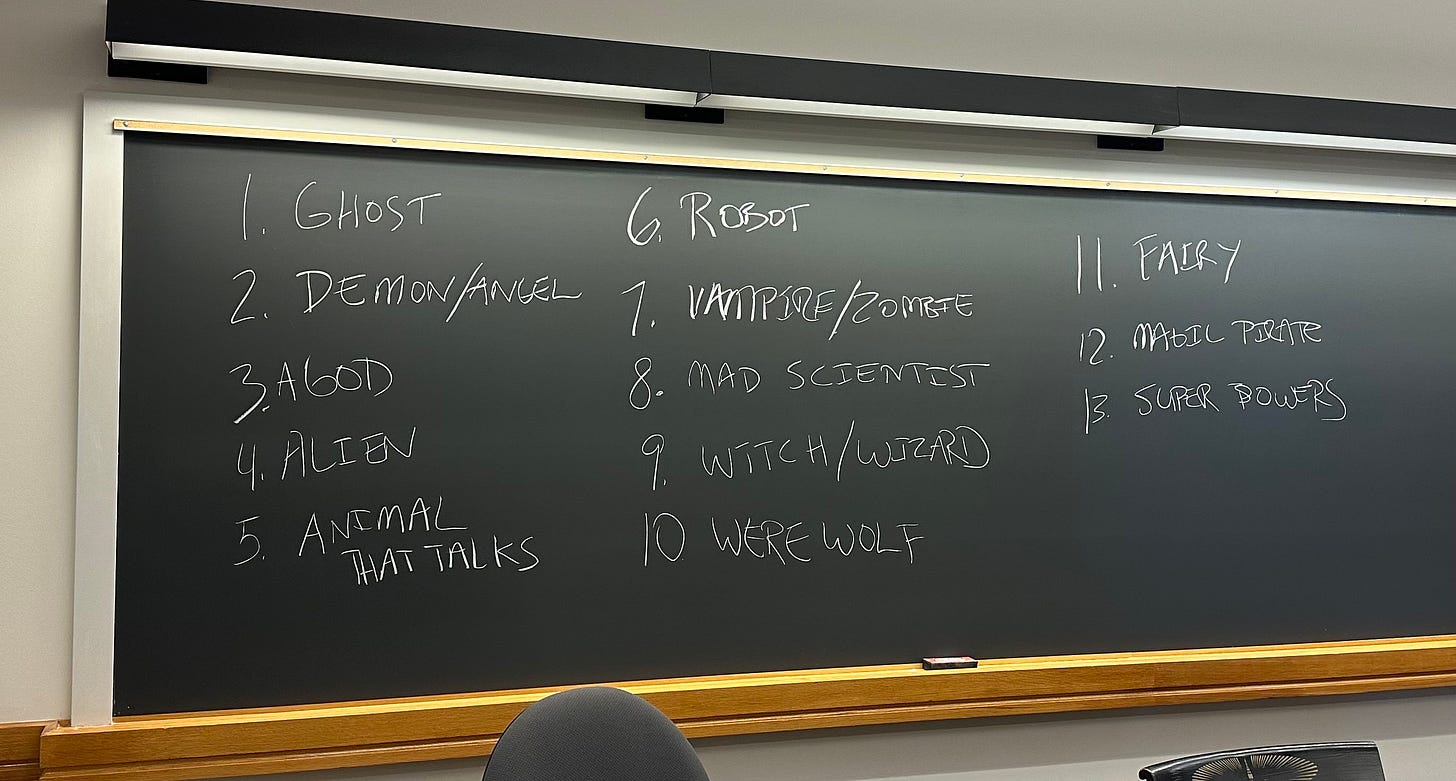

This fall I’ve been teaching a class that I’ve taught in some form or another since 2011, when I began it as a seminar on speculative fiction at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. I teach a much revised version of it now to undergraduate students. The above photo is a list that will make sense below when you reach the five part writing prompt.

I taught the class because it was always there in my fiction. The Queen of the Night is a novel of alternate history, for example, speculating on the past, inventing a character and her episodes inside of the history of the Second Empire and the end of that empire. And Edinburgh reinvents the myths of the fox demon shape changer seducer. The thinking I do with class has certainly since shaped my criticism. But when I say I was thinking together with students, I personally was thinking of a novel that I haven’t let myself try to write except in fits and starts since the 1990s. And as I get to the end of the novel I’m finishing I find myself thinking of that one next. I shouldn’t wait much longer. In any case, if you’d like to play along, here are some texts and that writing prompt.

The first syllabus had this description:

With the idea that the future and the past are, for the living,seen through acts of imagination, we will read a mix of historical fiction and speculative fiction that make use of the past or future to reach past the conventional taboos of a culture—incest, murder, adultery—and find their way into the real taboos, harder to speak of or describe. These novels mean to portray great shifts within a culture’s moral structure, and set characters within historic crises, imaginatively predicted ones, or imaginative acts that replace our history as a way to comment on it. And they dress what they fear as heroes and monsters.

We will read for technique, discussing writing our way into the past or future, the implications of inventing or reinventing a nation, the effects these novels achieve, their structures, and the narrative and aesthetic strategies employed in their creation.

The first reading list was extensive, perhaps too long, but I was dreaming.

Orlando, Virginia Woolf

Wizard of the Crow, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o

Autobiography of Red, Anne Carson

The Children’s Hospital, Chris Adrian

Master Georgie, Beryl Bainbridge

The Line of Beauty, Alan Hollinghurst

The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, Michael Chabon

Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro

The Known World, Edward P. Jones

Pym, Mat Johnson

I added some other details to the description that seemed necessary. A quote from William Gibson was helpful:

Interviewer: You made your name as a science-fiction writer, but in your last two novels you’ve moved squarely into the present. Have you lost interest in the future?

William Gibson: It has to do with the nature of the present. If one had gone to talk to a publisher in 1977 with a scenario for a science-fiction novel that was in effect the scenario for the year 2007, nobody would buy anything like it. It’s too complex, with too many huge sci-fi tropes: global warming; the lethal, sexually transmitted immune-system disease; the United States, attacked by terrorists, invading the wrong country. Any one of these would have been more than adequate for a science-fiction novel. But if you suggested doing them all and presenting that as an imaginary future, they’d not only show you the door, they’d probably call security.

In 2007, William Gibson, one of science fiction’s most visionary writers—the man who first imagined, and thus invented, virtual reality—gave up on writing science fiction for almost a decade, saying reality had outstripped science fiction.

But readers and writers have since run to the genre he left behind for the capacity it has to make sense of the world, as strange as it is and as it is becoming, and now he has returned to this work also. We see the result especially in speculative fiction—a tradition of literary novels and stories that draws on science fiction, magical realism, myth, YA and alternate history, using the fantastic and the inhuman to make sense of and describe or inspire the human.

Additional Texts over the years as the course traveled with me to other schools and contexts (like an undergraduate setting) include

Hav, Jan Morris

Her Body And Other Parties, Carmen Maria Machado

Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler

Severance, Ling Ma

White Cat Black Dog, Kelly Link

Friday Black and Chain Gang All-Stars, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

The Bloody Chamber, Nights At The Circus and The Infernal Desire Machines of Dr. Hoffman by Angela Carter

A People's Future of the United States, edited by Victor LaValle

The Tiger’s Wife,Téa Obrecht

Zone One, by Colson Whitehead

Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel

Meet Us By The Roaring Sea, Akil Kumarasamy

Some single stories and essays taught over the years:

“The Lady In The House of Love,” by Angela Carter

“Light Spitter,” by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

"The Last Days of the Famous Mime," by Peter Carey

"The Holes in the Mask," Jean Lorrain;

"The Baroque and the Marvelous Real," by Alejo Carpentier

"A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings," by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

"Mothers, Lock Up Your Daughters Because They Are Terrifying," by Alice Sola Kim

"The Machine Stops," by E. M. Forster

"The Prospectors," by Karen Russell

"A Tiny Feast," by Chris Adrian

"Evidence," by Kaitlyn Greenidge

"A Voice in the Night," Steven Millhauser

"Darkness," by Andrew Sean Greer

"Making Love in 2003," by Miranda July

"He Was No Good And He Had To Die," by Colin Winette

"Standard Loneliness Package," by Charles Yu

"The Husband Stitch," by Carmen Maria Machado

The Lost Performance of the High Priestess of the Temple of Horror, by Carmen Machado

“Black-Eyed Women,” by Viet Thanh Nguyen

“What Ghost Stories Taught Me About My Queer Self,” by Nell Stevens

“Ghosts of the Tsunami,” by Richard Lloyd Perry

“Sea Oak,” by George Saunders

“The Devil Swam Across The Anacostia River,” by Edward P. Jones

“St. Lucy’s Home For Girls Raised By Wolves,” by Karen Russell

“History of the New World,” by Adam Garnet Jones

"12 Fundamentals to Writing the Other," by Daniel José Older

“Johnny Mnemonic,” by William Gibson

“Immortality,” by Yiyun Li

“Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned,” by Wells Tower

“The Pink House,” by Rebecca Curtis

“The Enchanted Hand,” by Gérard de Nerval

“The Ghost and the Bonesetter,” by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

“Vampires In The Lemon Grove,” by Karen Russell

“Paranoia,” by Saïd Sayrafiezadeh

“This Appointment Occurs In The Past,” by Sam Lipsyte

And now we get to the photograph, taken in class a month ago.

For the interested, in several parts, a writing prompt. The pieces written each week and then assembled, over four or five weeks. I just gave the exercise a name:

The Changeling

Take a seemingly ordinary and even commonly told story. The child who has to go their grandparent's funeral. The babysitter who gets hit on by the father of the family she works for. The frat party gone wrong. The runaway. Then, replace one of the characters in some way with one of the following:

1. GHOST 2. DEMON/ANGEL 3. A GOD 4. ALIEN 5. ANIMAL THAT TALKS 6. ROBOT 7. VAMPIRE/ZOMBIE 8. WITCH/WIZARD 9. MAD SCIENTIST 10. WEREWOLF 11. FAIRY 12. MAGIC PIRATE 13. SUPERHERO/SUPERPOWERS

And if you don't see what you're looking for on the list, make something up but what we are looking for is how does a "normal" story change when one of the normal values is subverted? What happens if the child who goes to the grandparents' funeral has become a god? Or what happens if the babysitter is a ghost? What if the young woman at the frat party is a witch, intent on revenge? Or a vampire preparing to feed? Why has the runaway run away, or are they a robot? You are looking for the substitution that gets you excited, or makes you laugh, or both. Where your curiosity is so intense that you have to know what happens and so you write it.

Now write a beginning to your story. Try for at least 250 words.

What Rules This World?

Much of creating a draft involves taking a leap with your writing and then looking back to see how to fulfill the implications of what you've invented. Read back over you results for writing prompt 1. What clues are visible to you about the world this story inhabits and how it makes the story possible? What is implied that you could follow up on, and what more can you add to the story, by way of a next section or a needed character or development to a situation? And how are you presenting the rules of the world to the reader, and do you need to do more? Less? Something different?

Write 250 words further into the story using this sense of the story as a guide, or for those of you who have already written a full draft, revise at least 250 words of that draft based on what you find and post that here.

What Changes Them, And Who Or What Do They Change?

This far into the story it is time for your characters to make choices based on what has happened to them and their sense of what they are becoming. All of us are a mix of what we can and cannot change, and what we know to be true about that and what we are prepared to test of that sense of the truth.

So... Make a list of what your main character or characters can change about themselves and what they cannot, and then make a third list of what they don't know they can change, and a fourth--what they don't know they can't change. A fifth list, possibly short: What will they try to change?

And how can this story bring them into meaningful encounters with these truths? It's often said that characters are shaped by what they want, by their desires, and I think this is true, but I think they are shaped more by how those desires urge them to grow, to reach past where they are, to test their limits.

After you make out these lists, write the next 250-500 words of the story.

What Cannot Be Taken Back?

The short story is typically about a transformation or “something that has happened to someone,” as Rust Hills says in his classic writing guide, Writing In General And The Short Story In Particular. “A story... is dynamic rather than static: the same thing cannot happen again. A character is capable of being moved, and is moved, no matter in how slight a way.”

In class the other day, I described the Story Alphabet structure, ABDCE (Action Background Development Climax Ending) and I was talking about the ways to approach a climax in a story. I find the word repellent to be honest and spoke of how I preferred the idea of What Cannot Be Taken Back. What change occurs that the character must contend with, typically chosen by them or a result of their choices say in the face of a change they perhaps did not choose but may have put in motion.

Looking at your story, and having done the previous exercise, what will challenge the character(s) such that they change in these ways that cannot be undone? How does the story get them there and look at the transformation? And how do they contend with it?

Write either a summary of your thinking or even better, write scenes. Try for 250 words minimum.

How Does It End?

Ending a story might feel impossible to do but you begin by asking yourself the following questions:

Is my Main Character the subject of the story, or are they less central, and is the story organized around their actions, their POV, or both?

Who does the story's climax happen to or because of, and how does that change your sense of the story's final moments?

How can the tensions created by the story's antagonist create the ending?

Is there a minor character from earlier in the story who can return and be a major part of this ending?

Does it help at all to try to return in some subtle way to the story's beginning?

Consider using, as a model, the ending to a favorite story, either from tfrom your own reading history. Examine the construction: does it simply cut off, and if so, how? Is there a gathering up of themes and plot details left hanging from earlier? Or does the story look into the future of the story's characters?

The classic ending for a short story often supplies a detail that changes the reader's sense of the entire story--introducing some previously unanticipated shape to the events that can be seen to have been building all along. Of these previous approaches if none speaks to you consider that. Does the story have a shape that surprises you and can you finish that shape, the one you both wrote and did not anticipate?

Re-read the draft and look for a sense of trajectory. Avoid introducing new themes at the end, and new characters also, or introduce them only if they emerge from the momentum with the power to bring these previous pages to this conclusion.

Draft a sketch for an ending then, as long as it has to be.

Until next time,

Alexander Chee

My mind is racing with bits and pieces of scattered ideas since reading this-thank you so much for your generosity! I would love to take this class if you offer it on line. The concept that our present had become more fantastical than our imagined futures - it’s terrifying in its truth.

I wish I could take your class!!!! It sounds so awesome.