Today’s letter picks up a series of writing prompts begun last year and greatly delayed. Thanks to all of you for your patience. The first letter of that series looks at

’ novel All This Could Be Different, a novel about the way friendship and mutual aid can help undo the trauma of attempts at American rugged individualism under capitalism. A second is about E. M. Forster’s Maurice, a novel about social class, compulsory heterosexuality, Empire at home and the closet. These writing prompts are not the same as some I’ve offered here as they analyze how a novel affects the reader and how the writer constructed the novel to do so—and the effort hopes to offer insights into how to do the same.Some background: I met Ocean Vuong first on Facebook in 2009. He had found me through an interview I did with my friend Christine Hyung-Oak Lee for the magazine The Kartika Review and he wanted to thank me for my comments there about writing and the diaspora there. No questions for me, just a thanks, but that was also illuminating. Ocean is still like this. A persistent illumination.

He was at the time an undergraduate at Brooklyn College, and publishing his first poems. I came across those first messages six years later when preparing to interview him for the Swedish magazine Bon, who had invited us to have a conversation on the occasion of his debut collection of poems.

Our conversation that day was expansive and only about half of it fit into the feature. Lines from what he said then return to me often. Ocean has consistently treated me with loving respect, and I will say I was moved partly because I didn’t expect it, somehow. And so I got to reflect on why that was.

But for the rest of this letter I will refer to him as Vuong so as not to seem too familiar.

This comes as Ocean’s second novel, The Emperor of Gladness, is soon to publish. You can preorder that novel here. I would ordinarily paywall this but in celebration of the new novel I have decided to keep it free. Many thanks to my subscribers who make efforts like this possible.

*

As I went back over the Bon interview again to write about the novel, I found this:

Alexander What were some of the forms that interested you in the process of composing the book?

Ocean I was very interested in… I don’t know if this is the antithesis of form, but I wanted to pursue a restlessness of form.

Alexander A restless form?

Ocean Yes. Where every poem was trying on different clothes. There’s one poem in there, “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous,” where every section is labelled “I”? So that it’s attempting itself over and over. What happens when the form doesn’t work? I was interested in seeing, experimenting, with these containers. Can a country contain a restless mind, a restless person, a different person, a queer person? Can a form contain a queer obsession? I guess that was what I was interested in. I didn’t want to be comfortable in one form or another.

In 2018, Vuong published his debut novel, the title shared with the poem that was “attempting itself over and over.” The novel begins with the line, “Let me begin again.” The poem showing up in new clothes again. I like that idea for this novel, the novel like a showgirl changing backstage and coming back out to give a whole new performance.

Vuong published an essay in The New Yorker close in some ways to the first chapter. I taught it to my first year seminar students that year, I remember, because it is an open letter, a form that asks the reader to engage with an intimate context that does not appear to have them in mind even as it is also offered in order to engage them. A paradox of a kind.

The novel is then also an open letter and re-engages the material of the poem as well as the essay. A letter in English written to a mother who does not read English by a son who, we learn eventually, is trying to answer her question to him about what it is like to be a writer.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous was an international bestseller, and by 2022 it had sold over 1 million copies world-wide in editions available in 40 languages. It is also a highly experimental novel, and so perhaps we can say it was a successful experiment. But I have often felt, when listening to people speak of the novel, that perhaps they had not read the novel or at the least had misunderstood it and soon it was so successful it also became a casual target for resentment from people who found the astonishing phenomenon around the novel bewildering. Vuong has never had a Twitter presence I knew of, and never bothered to respond to things there, though he has sometimes taken to Instagram to do so.

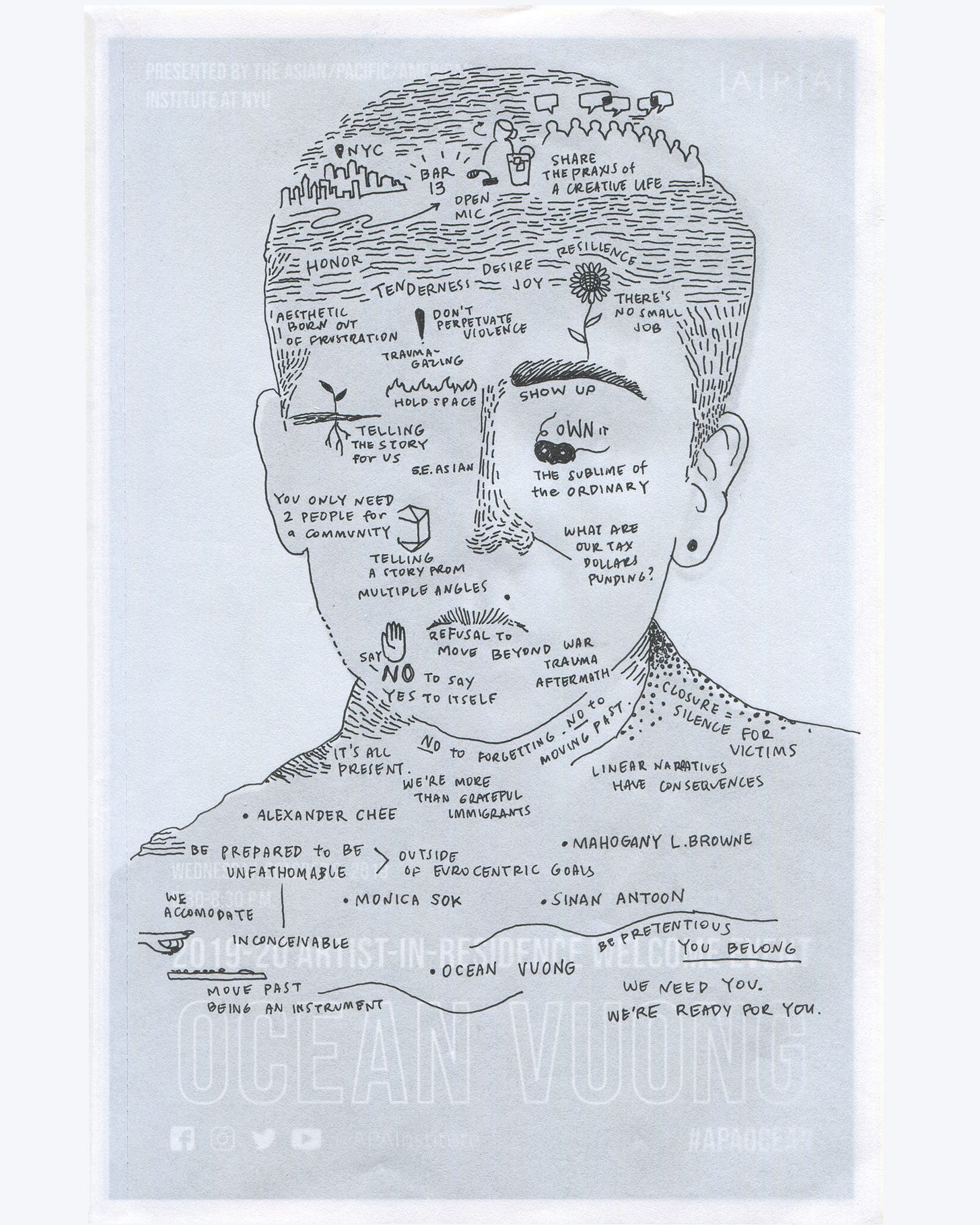

Vuong used his book tour to conduct a kind of teach-in, place to place, thinking out loud, conversation by conversation, how literary life is conceived of for Vietnamese American writers, refugee writers, Asian and Asian American writers, queer writers and writers in general. The artist Lilly Lam did this sketch below in her notes from an event he did that year in New York City, sketching notes with a poster for the event visible faintly underneath. I am using it here with her permission. I was a guest speaker at this event, along with Monika Sok, Sinan Antoon, Mahogany L. Browne. We were at the New York University Center for Refugee Poetics. It was a beautiful night.

I remember when he said to the audience, “Be prepared to be unfathomable.” This was his answer to the question of what advice did he have for Asian and Asian American artists. To be prepared to make art that was difficult, challenging in ways that were not specifically about challenging a power structure but about that were also about ways of being, ways of describing the world, inventing worlds, calling to new worlds, calling them into being. Ways of being in community. Ways of telling a story, writing a poem, of being with an audience. He understood himself as trying to inspire not just younger writers but all of us. And I remember him saying, as Lilly wrote above, “We need you. We’re ready for you.”

*

At the time, Vuong himself did in interviews and profiles describe his process. In his essay for Lit Hub, The 10 Books I Needed To Write My Book, he offers many insights into what we might call anything like a recipe for this novel. There’s typically a stack of books that goes into any book, the books you keep on your desk or nearby.

In Kevin Nguyen’s New York Times profile of him, Vuong describes his intention as regards the open letter this way:

In order to read the book, people have to eavesdrop as a secondary audience upon a conversation between two Vietnamese people.

This is what I would tell her if I could, the narrator Little Dog seems to say. But I can only tell you.

I have joked that there are secrets you can only tell the internet. There are also secrets you can only tell a novel. That informs this effort, it seems to me.

Another experience of the novel I don’t see described as much: Little Dog has lived a life full of the voices of his mother and grandmother and is testing the use of his own voice among them, from within that experience, as the novel progresses. He was raised by these women and their stories of the Vietnam War and America, brought up with their PTSD, even by it, within it. Their nightmares, he had to learn them, learn what we might see as their delusions. This mix of what they cannot remember, what they cannot forget, what they refuse to say and what they cannot hold back from speaking aloud, when he acts as their translator, as he puts it, this is what he had to learn just to speak with them, live alongside them. Sometimes he acts a role inside of a drama they are experiencing just to be there.

This novel is perhaps the most well-known literary form in the US to make use of kishōtenketsu as a structural device. Vuong has spoken extensively about how as a Buddhist he was drawn in part by the structure’s relationship to Buddhist values. The structure is common in China, Korea and Japan, and perhaps familiar to you from the work of Hayao Miyazaki, but it is also a structure commonly used in Japanese Horror films like Why Don't You Play In Hell, a film that breaks the form down as it performs it.

Vuong described his decision to use the structure in that New York Times profile.

“It insists that a narrative structure can survive and thrive on proximity alone. Proximity builds tension.”

And in this conversation at the Paris Review with Spencer Quong, on the topic of the novel:

I think that’s what a novel is, at its core, one person trying to know themselves so thoroughly that they realize, in the end, it was the times they lived in, the people they touched and learned from, that made them real.

This is why I chose the novel as the form for this project. I wanted the book to be founded in truth but realized by the imagination. I wanted to begin as a historian and end as an artist. And I needed the novel to be a praxis toward that reckoning.

This book is as much a coming-of-age story as it is a coming-of-art. I would say that I begin with the voices of those I care for, family or otherwise, and follow them until they drop off, until I have to create them in order to hear them. My writing is an echo. In this way, On Earth is not so much a novel, but the ghost of a novel. That’s the hope anyway.

And then a few moments later, there is this exchange, on writing about queer sex:

INTERVIEWER

The novel casts light on love and sex between men—between a white boy and an Asian boy in America, specifically. I keep returning to these lines: “I thought sex was to breach new ground, despite terror, that as long as the world did not see us, its rules did not apply. But I was wrong. The rules, they were already inside us.” There’s no false promise of relief from the rules by x date—instead, only clarity, and bearing witness. Were there aspects of writing about queer sex and love that surprised you?

VUONG

Yes, it did surprise me, mostly because I wanted to arrive at queer joy—but discovered that I wanted to do so without forsaking the very real and perennial presence of danger that queer bodies face simply by existing. There is a call, rightfully, for literature to make more room for queer joy, or perhaps even more radically, queer okayness. But I did not want to answer that call by creating a false utopia—because safety is still rare and foreign to the experiences of the queer folks I love, who are also often poor and underserved. I didn’t want to pretend to be happy just because straight people were tired or bored of our struggle.

The novel insists that there is power, and with it, agency, in survival—which includes the interracial tensions you speak of—because trauma is still an integral reality for queer folks. But these bodies do know joy, and they know it by acknowledging and honoring the tribulations they outlived. We often think of survival as something that merely happens to us, that we are perhaps lucky to have. But I like to think of survival as a result of active self-knowledge, and even more so, a creative force.

The novel is very much about the sex, love and intimacy Little Dog finds with his friend Trevor, who becomes his first important lover. Little Dog describes how they explore their bond and the turn the novel takes, in the four act structure of kishotenketsu, seems to me to be when Little Dog learns of Trevor’s death, and his life undergoes an alteration he didn’t anticipate.

You may also enjoy this breakdown of the kishotenketsu form by

at his Substack, Counter Craft.To make use of the On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous Writing Prompt, then, try to imagine a story making use of most, if not all, of the following, though perhaps it is better to say, do you have a story that might be mapped this way? Can the points below offer moments of reflection and analysis? This prompt is not an invitation to people to co-opt the stories of the marginalized, in other words.

A story with no villains, no victims, no arcs of ‘rising action’.

The setting is an American city with an immigrant population created in part or entirely by the wars America has fought in, and the narrator is someone from one of those communities.

The characters are working class, all of them, and at least bilingual. There should be two or more languages spoken.

Vuong’s Little Dog is mixed race Asian American, Vietnamese American. He lives with his mother and grandmother.

The American military is wound throughout the story’s action, past and present if not future, and intimately so.

Should the story be a fragmented narrative that describes what the narrative could not describe if it was an unbroken linear narrative, chronologically?

The novel’s leaps through time and the ways Vuong describes, say, the grandmother, believing in Hartford, CT that she and Little Dog are in a helicopter in Viet Nam, and he plays along to make the story possible, their life possible, in those moments. The story creates a kind of irony, at least a doubling, maybe more times than that—the story of the grandmother, the grandson, the war, the countries involved, all meet. The story is like traveling the facets of a prism.

The fragments make the story more rather than less connected—not a stream of consciousness but a guided tour of one, precise, pinpointed, like a map. And the narrator is not just a translator for the languages in the story but also a guide through time. The intimate time of the family.

The novel makes vivid use of the present tense, especially the way a present tense narrative imagines time as a volume, as a place to which you can return through the present tense.

What stories can you tell with a narrator who has lived with the stories of others such that they reverberate through them, as if they were their own lived experiences? Stories told by relatives, stories told by a lover, stories told repeatedly until the narrator is full up of these other lives? How can this make up the fabric of the text that the narrator creates?

Try the story in the 2nd person, a specific You conjured so that reader is eavesdropping on a one-sided conversation between two other people but is also drawn inside an intimate context they might otherwise never have access to and all of the stories that come along with that. Is the you a specific person, as in Vuong’s novel, or is it the narrator speaking to themselves, or it is a reader?

Give attention to the moments of communication, the scenes, especially those moments that occur across languages and differences in experience.

Explore form by borrowing a form from another art form or genre, especially one that helps the story to express the values of the author or narrator spiritually.

As I said, the point is not so much to imitate the novel as to liberate a story you might not otherwise tell. May it be so.

Until next time,

Alexander Chee

This is just great. So thoughtful and well conceived. I love it as a form of review.

Thank you for reminding me of the gentle fierce brilliance of Ocean Vuong